Chapter 1

Introduction to Computational Physics

"The pursuit of knowledge and the application of new tools can transform entire fields and open up new possibilities." — Isamu Akasaki

Chapter 1 of CPVR provides a comprehensive introduction to computational physics with a focus on utilizing Rust for implementing various computational methods. It begins by defining computational physics, tracing its historical development, and emphasizing its importance in solving complex physical problems. The chapter then introduces Rust, highlighting its unique language features, safety, and performance benefits. It covers Rust’s application in scientific computing, including key libraries and optimization techniques. Practical case studies illustrate the implementation of computational algorithms in Rust, showcasing its efficiency compared to other programming languages. The chapter concludes with a discussion on future trends, exploring how Rust can contribute to advancing computational physics and addressing emerging challenges. Overall, Chapter 1 sets the stage for understanding how Rust can be effectively used in the field of computational physics, bridging theoretical concepts with practical implementation.

1.1. Overview of Computational Physics

Computational Physics is a field that integrates physics, mathematics, and computer science to solve complex physical problems using computational methods. Unlike traditional branches of physics, which rely heavily on analytical models and experimental data, computational physics employs numerical algorithms and computer simulations to model and analyze systems that are otherwise intractable through conventional means. This interdisciplinary approach allows researchers to explore a vast range of physical phenomena, from the behavior of subatomic particles to the dynamics of galaxies, with precision and scalability.

Key areas of computational physics.

The historical development of computational physics dates back to the early 20th century when physicists began utilizing mechanical calculators to solve complex equations that were beyond the scope of manual computation. With the advent of digital computers in the mid-20th century, the field witnessed a significant evolution. The introduction of numerical methods such as finite difference, Monte Carlo simulations, and molecular dynamics revolutionized the way physicists approached problem-solving. These advancements allowed for the exploration of more sophisticated systems, leading to new insights and discoveries across various domains of physics.

In the context of modern physics, computational approaches have become indispensable, particularly in addressing problems that are too complex for analytical solutions or experimental validation. For instance, modeling the behavior of quantum systems with many interacting particles, simulating the evolution of galaxies over billions of years, or predicting climate change through atmospheric dynamics, all require the computational power and precision that only advanced algorithms and simulations can provide. Computational physics enables scientists to create detailed models, conduct virtual experiments, and visualize complex phenomena, which not only enhance our understanding of the physical world but also contribute to technological advancements and engineering innovations.

The applications of computational physics are vast and span across multiple domains. In astrophysics, it is used to simulate the formation and evolution of galaxies, study black hole dynamics, and model stellar interactions. In condensed matter physics, computational methods help in understanding the electronic properties of materials, guiding the development of new materials with desired properties. Quantum mechanics benefits from computational physics by enabling the solution of the Schrödinger equation for multi-particle systems, which is crucial for the design of quantum computers. In plasma physics, simulations of nuclear fusion reactors are conducted to optimize energy output and containment strategies. Additionally, climate science relies heavily on computational models to predict future climate scenarios and assess the impact of various factors on global temperatures.

Rust, a systems programming language known for its performance, memory safety, and concurrency capabilities, offers a robust platform for implementing computational physics simulations. Its ownership model ensures memory safety without sacrificing performance, making it ideal for high-performance computing tasks required in complex simulations. Rust’s ecosystem includes powerful crates such as ndarray for numerical computations, nalgebra for linear algebra operations, and rayon for parallel processing, all of which are essential for developing and scaling computational models efficiently.

For example, in a molecular dynamics simulation, Rust allows for the efficient handling of large datasets representing particles and their interactions. The language’s concurrency features enable the parallel processing of these particles, significantly speeding up the computation. Moreover, Rust's strict memory management system ensures that simulations run safely without data races or memory leaks, which are critical for long-running simulations that demand high accuracy and reliability.

In summary, computational physics plays a vital role in modern science, offering tools and methods to solve complex problems that are beyond the reach of traditional physics approaches. The use of Rust for practical implementation in this field leverages the language's strengths in performance and safety, making it an excellent choice for developing advanced computational models that contribute to our understanding of the physical universe.

1.2. Introduction to Rust Language

Rust is a systems programming language that has garnered significant attention in the scientific computing community for its unique combination of performance, safety, and modern language features. At the core of Rust are principles that set it apart from other languages traditionally used in computational physics, such as Fortran, C, C++, and Python. These principles include ownership, borrowing, and lifetimes, which together form a robust memory management system that eliminates common issues like null pointer dereferencing, data races, and memory leaks without the overhead of garbage collection.

For those interested in delving deeper into Rust and mastering its concepts, a valuable resource is the online book "The Rust Programming Language," available at [trpl.rantai.dev](https://trpl.rantai.dev). This comprehensive guide covers everything from the basics of Rust to advanced topics, making it an excellent starting point for both beginners and experienced programmers looking to harness the full power of Rust in computational physics and beyond.

The ownership system in Rust is fundamental to understanding how the language ensures memory safety. In Rust, each value has a single owner at any given time, and when the owner goes out of scope, the value is automatically deallocated. This eliminates the need for manual memory management, reducing the likelihood of errors. Borrowing and lifetimes are mechanisms that allow references to data without transferring ownership, enabling safe and concurrent data access. Borrowing rules ensure that while data is being mutated, no other references can access it, preventing data races. Lifetimes, on the other hand, are a way of describing the scope of references, ensuring that references do not outlive the data they point to, thereby preventing dangling pointers.

When comparing Rust to other languages commonly used in computational physics, several advantages become apparent. C and C++ are known for their performance and control over system resources but are prone to memory management errors, which can lead to undefined behavior and security vulnerabilities. Fortran, while still used in high-performance computing for its efficient handling of numerical operations, lacks the modern language features and safety guarantees that Rust provides. Rust combines the low-level control and performance of C and C++ with a type system that ensures memory safety and concurrency without sacrificing speed. This makes Rust particularly well-suited for scientific computing tasks that require both high performance and reliability.

Rust’s performance is on par with C and C++, largely due to its zero-cost abstractions, meaning that high-level constructs do not incur runtime overhead. This is crucial in computational physics, where simulations often run for extended periods and process large amounts of data. The language's safety guarantees are equally important in scientific computing, where the correctness of a simulation is paramount. Bugs related to memory corruption, which are common in C and C++, are virtually eliminated in Rust due to its strict compile-time checks. This reliability ensures that simulations are not only fast but also accurate and reproducible.

Setting up a Rust development environment is straightforward and can be accomplished on most operating systems with minimal effort. The first step is to install Rust using the official installer, rustup, which also manages toolchains and updates. Once installed, the basic syntax of Rust can be explored through writing simple programs. Rust’s syntax is modern and expressive, borrowing elements from other languages while introducing its unique constructs. For example, the let keyword is used to bind values to variables, and pattern matching is a powerful feature that allows for concise and readable code when handling different data structures. The Rust compiler, rustc, is highly informative, providing detailed error messages that guide developers in writing correct and efficient code.

In practice, setting up a computational physics project in Rust might involve creating a new Rust project using the cargo tool, which is Rust’s package manager and build system. Cargo simplifies dependency management, builds automation, and project organization, making it easier to manage complex projects typical in scientific computing. For instance, a basic project might involve creating data structures to represent physical systems, implementing algorithms for numerical simulations, and using Rust’s concurrency features to parallelize computations across multiple cores.

In conclusion, Rust offers a compelling environment for computational physics due to its combination of performance, safety, and modern programming features. Its ownership and borrowing system, alongside its strong type system, ensure that programs are free from many of the common pitfalls associated with low-level programming. When compared to traditional languages like C, C++, and Fortran, Rust stands out for its ability to provide both speed and reliability, making it an excellent choice for scientists and engineers looking to implement complex simulations and algorithms. Setting up a Rust environment is straightforward, and the language's syntax and tools support the development of efficient and robust computational physics applications.

1.3. Rust for Scientific Computing

Rust has rapidly gained traction in the scientific computing community, thanks to its combination of performance, safety, and modern language features. For scientific computing, Rust offers a variety of libraries and crates specifically designed to handle numerical computations, linear algebra, and other essential tasks in computational physics. Key among these are ndarray and nalgebra, which provide powerful tools for working with arrays, matrices, and other mathematical structures critical for simulations and data analysis. For those interested in deepening their understanding and practical skills in Rust for scientific computing, the book Numerical Recipes via Rust (NRVR) from RantAI is an excellent resource. This book offers comprehensive coverage of numerical methods and their implementation in Rust, serving as a valuable guide for leveraging Rust's capabilities in computational physics and beyond.

The ndarray crate is a cornerstone for numerical computing in Rust, offering N-dimensional arrays that can be used to represent and manipulate large datasets, similar to NumPy in Python. It supports a wide range of operations, including element-wise arithmetic, matrix multiplication, and advanced slicing. ndarray is highly versatile, making it suitable for various applications, from simple data storage to complex mathematical operations required in computational physics. Its design emphasizes both performance and safety, ensuring that computations are not only fast but also free from common errors like out-of-bounds access.

Complementing ndarray is nalgebra, a general-purpose linear algebra library that provides tools for dealing with vectors, matrices, and transformations. nalgebra is optimized for both small and large matrices, making it suitable for tasks ranging from simple linear transformations to large-scale simulations involving thousands of variables. The crate’s flexibility allows it to handle both statically and dynamically sized matrices, providing a robust framework for implementing algorithms that are foundational in computational physics, such as solving systems of linear equations, eigenvalue problems, and performing numerical integration.

Implementing basic algorithms and data structures in Rust for computational physics problems involves leveraging these crates while adhering to Rust’s principles of safety and performance. For example, consider the implementation of a simple particle simulation. The particles' positions and velocities can be stored in ndarray arrays, and nalgebra can be used to perform matrix operations to update their states based on physical laws. Rust’s strong type system and memory safety guarantees ensure that the simulation is free from common errors like memory leaks or race conditions, which are crucial for the accuracy and reliability of the simulation.

Performance is a key consideration in scientific computing, and Rust excels in this area through various optimization techniques. Rust’s ownership system eliminates the need for garbage collection, allowing for predictable performance. Additionally, Rust’s support for zero-cost abstractions means that high-level code, such as iterators and functional programming constructs, does not incur additional runtime costs. Rust’s ability to perform inlining, loop unrolling, and other compile-time optimizations ensures that scientific computations are executed as efficiently as possible. For more complex optimizations, Rust allows for fine-grained control over memory layout and data access patterns, enabling developers to maximize cache usage and minimize memory access latency.

Another strength of Rust in scientific computing is its ability to interface with other languages and tools commonly used in the field. Rust’s Foreign Function Interface (FFI) allows for seamless integration with C and C++ libraries, enabling the reuse of existing high-performance libraries and tools. This is particularly valuable in scientific computing, where leveraging established libraries like LAPACK for linear algebra or FFTW for Fourier transforms can significantly enhance the performance and capabilities of Rust-based projects. Additionally, Rust can interoperate with Python through libraries like pyo3 and cpython, allowing developers to combine Rust’s performance with Python’s extensive ecosystem for data analysis and visualization.

In practice, setting up a Rust project for scientific computing might involve using Cargo to manage dependencies on crates like ndarray, nalgebra, and others. Implementing a computational physics algorithm would typically start with defining the data structures in Rust, ensuring that they are optimized for both memory and performance. Algorithms can then be implemented using Rust’s powerful abstractions, taking advantage of the language’s concurrency features to parallelize computations where applicable. Finally, interfacing with existing tools and libraries can be done through FFI or embedding Rust code in a Python workflow, ensuring that the resulting application leverages the best of both worlds.

In summary, Rust offers a robust and high-performance platform for scientific computing, supported by a growing ecosystem of libraries and tools tailored for numerical and computational tasks. By implementing basic algorithms and data structures in Rust, developers can achieve both safety and performance, essential for the complex and demanding nature of computational physics. With its ability to interface with other languages and tools, Rust stands out as a versatile choice for building modern scientific computing applications.

1.4. Case Studies and Examples

To fully appreciate the power and versatility of Rust in computational physics, it is essential to explore practical examples and case studies that demonstrate how real-world problems can be solved using Rust. These examples not only showcase Rust's capabilities but also provide a clear understanding of how computational models are implemented, validated, and optimized for efficiency and reliability.

One practical example in computational physics is the simulation of planetary motion, a classical problem that involves calculating the gravitational interactions between celestial bodies. Using Rust, the implementation of this simulation leverages its strong type system and memory safety features to ensure accurate and efficient calculations. The positions, velocities, and masses of the planets can be represented using Rust’s ndarray crate, while the numerical integration of their trajectories can be performed using methods like the Runge-Kutta algorithm. Rust’s performance is evident in how it handles the intensive computations required for simulating interactions over long periods, ensuring that the simulation remains both fast and accurate.

Here's a simple example of how you might implement a basic simulation of planetary motion in Rust:

use ndarray::{Array1, Array2};

const G: f64 = 6.67430e-11; // Gravitational constant in m^3/(kg s^2)

/// Computes the acceleration on each body due to the gravitational forces from every other body.

fn calculate_acceleration(positions: &Array2<f64>, masses: &Array1<f64>) -> Array2<f64> {

let n_bodies = positions.nrows();

let mut accelerations = Array2::<f64>::zeros((n_bodies, positions.ncols()));

for i in 0..n_bodies {

for j in 0..n_bodies {

if i != j {

let dx = positions[(j, 0)] - positions[(i, 0)];

let dy = positions[(j, 1)] - positions[(i, 1)];

let distance_squared = dx * dx + dy * dy;

let distance = distance_squared.sqrt();

// Avoid division by zero for extremely close bodies

if distance > 1e-10 {

let force = G * masses[i] * masses[j] / distance_squared;

accelerations[(i, 0)] += force * dx / (distance * masses[i]);

accelerations[(i, 1)] += force * dy / (distance * masses[i]);

}

}

}

}

accelerations

}

/// Updates positions and velocities using a simple Euler integration scheme.

fn update_positions_and_velocities(

positions: &mut Array2<f64>,

velocities: &mut Array2<f64>,

accelerations: &Array2<f64>,

dt: f64,

) {

// Update velocities: v_new = v_old + a * dt

velocities.zip_mut_with(accelerations, |v, &a| *v += a * dt);

// Update positions: x_new = x_old + v_new * dt

positions.zip_mut_with(velocities, |p, &v| *p += v * dt);

}

fn main() {

let n_bodies = 3;

let dt = 0.01;

// Initialize positions for each body in 2D space (x, y).

// For example: Body 1 at (0.0, 0.0), Body 2 at (1.0, 0.0), and Body 3 at (0.5, 1.0).

let mut positions = Array2::from_shape_vec(

(n_bodies, 2),

vec![

0.0, 0.0, // Body 1

1.0, 0.0, // Body 2

0.5, 1.0, // Body 3

],

)

.expect("Error creating positions array");

// Start with zero velocities.

let mut velocities = Array2::zeros((n_bodies, 2));

// Example masses (in kg) for each body.

let masses = Array1::from_vec(vec![1.0e24, 1.0e22, 1.0e22]);

// Run the simulation for 1000 time steps.

for _ in 0..1000 {

let accelerations = calculate_acceleration(&positions, &masses);

update_positions_and_velocities(&mut positions, &mut velocities, &accelerations, dt);

}

println!("Final positions:\n{:?}", positions);

}

In this revised code, the zip_mut_with method is used to update the velocities and positions. This method allows us to perform element-wise operations between arrays, effectively applying the correct updates without causing type mismatches or compilation errors. Specifically, it updates the velocity by adding the product of acceleration and dt, and then it updates the position by adding the product of velocity and dt. The use of zip_mut_with ensures that the arrays positions and velocities are updated correctly while maintaining the correct dimensions and types expected by ndarray. This approach allows us to handle the calculations in a way that adheres to Rust's strict type system, ensuring that the simulation remains both accurate and performant.

In a more complex case study, consider the modeling of fluid dynamics using the Navier-Stokes equations, which describe the motion of fluid substances. Implementing this in Rust involves discretizing the equations using finite difference or finite volume methods, with the resulting system of linear equations solved using iterative techniques like the Conjugate Gradient method. Rust’s nalgebra crate is particularly useful here for handling the large sparse matrices that arise from these discretizations. The safety guarantees provided by Rust’s ownership and borrowing system ensure that the implementation is free from common pitfalls like race conditions and memory leaks, which are critical when running long and complex simulations.

use nalgebra::DMatrix;

use std::f64::consts::PI;

const N: usize = 10; // Grid size (NxN)

const RE: f64 = 100.0; // Reynolds number

const DX: f64 = 1.0 / (N as f64); // Grid spacing

const DT: f64 = 0.01; // Time step

const NU: f64 = 1.0 / RE; // Kinematic viscosity

/// Computes the Laplacian (a measure of diffusion) at grid point (i, j)

/// using a finite difference approximation.

fn laplacian(matrix: &DMatrix<f64>, i: usize, j: usize) -> f64 {

(matrix[(i + 1, j)] - 2.0 * matrix[(i, j)] + matrix[(i - 1, j)]) / (DX * DX)

+ (matrix[(i, j + 1)] - 2.0 * matrix[(i, j)] + matrix[(i, j - 1)]) / (DX * DX)

}

fn main() {

// Create zero matrices for the x-velocity (u), y-velocity (v), and pressure (p).

let mut u = DMatrix::<f64>::zeros(N, N);

let mut v = DMatrix::<f64>::zeros(N, N);

let mut p = DMatrix::<f64>::zeros(N, N);

// Initialize velocity fields with a simple vortex.

// For a vortex, one common initialization is u = -sin(pi*y) and v = sin(pi*x).

for i in 0..N {

for j in 0..N {

// Map grid indices to physical coordinates in [0,1]

let x = i as f64 * DX;

let y = j as f64 * DX;

u[(i, j)] = -y.sin();

v[(i, j)] = x.sin();

}

}

// Time-stepping loop

for _ in 0..100 {

let un = u.clone();

let vn = v.clone();

// Update interior grid points using the explicit Euler method.

for i in 1..N - 1 {

for j in 1..N - 1 {

u[(i, j)] = un[(i, j)]

- un[(i, j)] * (DT / DX) * (un[(i, j)] - un[(i - 1, j)])

- vn[(i, j)] * (DT / DX) * (un[(i, j)] - un[(i, j - 1)])

+ NU * DT * laplacian(&un, i, j);

v[(i, j)] = vn[(i, j)]

- un[(i, j)] * (DT / DX) * (vn[(i, j)] - vn[(i - 1, j)])

- vn[(i, j)] * (DT / DX) * (vn[(i, j)] - vn[(i, j - 1)])

+ NU * DT * laplacian(&vn, i, j);

}

}

// Simplified pressure correction step.

// Note: In a realistic simulation, the pressure correction would involve solving

// a Poisson equation, but here we use a simplified update.

for i in 1..N - 1 {

for j in 1..N - 1 {

let denominator = 2.0 * (u[(i + 1, j)] - u[(i - 1, j)] + v[(i, j + 1)] - v[(i, j - 1)]);

if denominator.abs() > 1e-10 {

p[(i, j)] = (u[(i, j)] * v[(i, j)] * DX * DX) / denominator;

}

}

}

}

println!("Final velocity field u:\n{}", u);

println!("Final velocity field v:\n{}", v);

println!("Final pressure field p:\n{}", p);

}

The provided Rust code demonstrates a simplified 2D fluid dynamics simulation using the Navier-Stokes equations, implemented through finite difference methods. It initializes velocity fields u and v and a pressure field p over a grid, then iteratively updates these fields based on the equations governing fluid motion. The laplacian function calculates the diffusion term necessary for modeling viscosity, and the main loop applies the explicit Euler method to update the velocities and a basic pressure correction step to enforce incompressibility. The code uses Rust's nalgebra crate to handle matrix operations efficiently, ensuring that the simulation runs safely and performs the necessary computations for each time step without encountering common issues like memory leaks or race conditions. The final state of the velocity and pressure fields is printed after completing the simulation steps.

A significant advantage of using Rust in these case studies is the ability to compare the implementations with those in other programming languages, such as C++, Python, or Fortran. For instance, while C++ might offer similar performance due to its low-level capabilities, Rust’s memory safety features provide a layer of reliability that C++ lacks without extensive manual management. On the other hand, Python, while easier to write and more accessible due to its rich ecosystem of scientific libraries, cannot match Rust’s execution speed and safety in highly demanding simulations. These comparisons highlight Rust's unique position as a language that combines the performance of low-level languages with the safety and modern features of high-level languages.

The efficiency of Rust implementations is often evident in benchmarks where the execution time and memory usage are compared across different languages. For example, in a simulation of heat transfer in a solid body, Rust’s implementation can be optimized to reduce memory overhead and execution time by carefully managing data structures and taking advantage of Rust’s concurrency features. This often results in performance that is on par with or superior to equivalent implementations in C++ or Fortran, while maintaining the safety and reliability that these languages might compromise without careful attention to detail.

This example illustrates a basic 2D heat transfer simulation in Rust using finite difference methods. In this model, the temperature distribution throughout a solid body is computed over time. The simulation sets up a grid where each element represents the temperature at that point in the body, and the evolution of the temperature field is determined by discretizing the heat equation with central differences for the spatial derivatives. The initial condition consists of a localized hot spot placed in the center of the grid, and as the simulation progresses, heat diffuses through the material according to the thermal diffusivity specified. This implementation leverages Rust’s ndarray crate to efficiently manage the two-dimensional grid and perform numerical updates, while Rust’s inherent memory safety and performance benefits ensure that the simulation runs reliably and accurately.

use ndarray::{Array2, s};

const NX: usize = 50; // Grid size in the X-direction

const NY: usize = 50; // Grid size in the Y-direction

const ALPHA: f64 = 0.01; // Thermal diffusivity

const DX: f64 = 1.0 / (NX as f64); // Grid spacing in the X-direction

const DY: f64 = 1.0 / (NY as f64); // Grid spacing in the Y-direction

const DT: f64 = 0.0001; // Time step

fn update_temperature(temp: &mut Array2<f64>) {

let mut temp_new = temp.clone();

for i in 1..NX - 1 {

for j in 1..NY - 1 {

let t_xx = (temp[(i + 1, j)] - 2.0 * temp[(i, j)] + temp[(i - 1, j)]) / (DX * DX);

let t_yy = (temp[(i, j + 1)] - 2.0 * temp[(i, j)] + temp[(i, j - 1)]) / (DY * DY);

temp_new[(i, j)] = temp[(i, j)] + ALPHA * DT * (t_xx + t_yy);

}

}

*temp = temp_new;

}

fn main() {

let mut temp = Array2::<f64>::zeros((NX, NY));

// Initial condition: a hot spot in the center of the grid.

temp[[NX / 2, NY / 2]] = 100.0;

// Run the simulation for a fixed number of time steps.

for _ in 0..1000 {

update_temperature(&mut temp);

}

println!("Final temperature distribution:\n{:?}", temp.slice(s![.., ..]));

}

This Rust code simulates 2D heat transfer in a solid body using a finite difference method. The temp array represents the temperature distribution across the grid, and the update_temperature function updates this distribution over time according to the heat equation, which is discretized using the central difference method for spatial derivatives. The loop in the main function runs the simulation for a fixed number of time steps, starting with an initial condition where a hot spot is placed in the center of the grid. The temperature values are updated iteratively, with each point on the grid affected by its neighbors, modeling how heat diffuses through the solid body. Rust’s ndarray crate is used to manage the grid and perform the necessary numerical calculations, while the memory safety and performance benefits of Rust ensure that the simulation runs efficiently and reliably.

Analyzing the results and validating computational models is another critical aspect of using Rust in computational physics. After implementing a physical simulation, the results must be compared against known analytical solutions or experimental data to ensure that the model is accurate. Rust’s precision in numerical computations, combined with its ability to handle complex data structures safely, ensures that the results are both accurate and reproducible. For example, in a case study of simulating the diffusion of particles in a medium, the results obtained from the Rust implementation can be validated against analytical solutions of the diffusion equation. This validation process is crucial in establishing the credibility of the computational model and ensuring that it can be trusted for further scientific investigations.

The code below demonstrates a sample implementation in Rust for simulating the diffusion of particles in a 2D medium using the finite difference method. The ndarray crate is used to manage the 2D grid representing the concentration field.

use ndarray::{Array2, s};

const NX: usize = 50; // Number of grid points in the X direction

const NY: usize = 50; // Number of grid points in the Y direction

const ALPHA: f64 = 0.01; // Diffusion coefficient

const DX: f64 = 1.0 / (NX as f64); // Grid spacing in the X direction

const DY: f64 = 1.0 / (NY as f64); // Grid spacing in the Y direction

const DT: f64 = 0.0001; // Time step

const TIME_STEPS: usize = 10000; // Number of time steps

/// Updates the concentration array using finite differences to approximate

/// the second derivatives in x and y directions.

fn update_concentration(concentration: &mut Array2<f64>) {

// Clone the current concentration to calculate the new values.

let mut concentration_new = concentration.clone();

// Loop over the interior of the grid to avoid boundary issues.

for i in 1..NX - 1 {

for j in 1..NY - 1 {

let d2c_dx2 = (concentration[(i + 1, j)] - 2.0 * concentration[(i, j)]

+ concentration[(i - 1, j)])

/ (DX * DX);

let d2c_dy2 = (concentration[(i, j + 1)] - 2.0 * concentration[(i, j)]

+ concentration[(i, j - 1)])

/ (DY * DY);

concentration_new[(i, j)] =

concentration[(i, j)] + ALPHA * DT * (d2c_dx2 + d2c_dy2);

}

}

*concentration = concentration_new;

}

fn main() {

// Initialize the 2D concentration grid with zeros.

let mut concentration = Array2::<f64>::zeros((NX, NY));

// Set the initial condition: a spike of particles at the center of the grid.

concentration[(NX / 2, NY / 2)] = 1.0;

// Perform the simulation over the specified number of time steps.

for _ in 0..TIME_STEPS {

update_concentration(&mut concentration);

}

// Print the final concentration distribution.

println!(

"Final concentration distribution:\n{:?}",

concentration.slice(s![.., ..])

);

}

This Rust code simulates the diffusion of particles in a 2D medium using the finite difference method to solve the 2D diffusion equation. The concentration array represents the concentration of particles at each grid point on a 2D grid. The update_concentration function updates this concentration over time by calculating the second spatial derivatives in both the x and y directions, using central differences. The initial condition places a spike of particles in the center of the grid. The simulation loop iterates for a set number of time steps, during which the particles spread out across the grid due to diffusion. The final concentration distribution is printed, showing how the particles have diffused throughout the 2D medium. This example illustrates how Rust’s ndarray crate can efficiently handle 2D numerical computations while ensuring the accuracy and safety of the simulation.

In conclusion, practical examples and case studies in computational physics demonstrate the effectiveness of Rust in solving complex problems. By implementing algorithms for physical simulations in Rust, researchers can achieve high levels of efficiency and reliability, which are critical for accurate and scalable simulations. Comparisons with other programming languages further underscore Rust’s advantages, particularly in terms of safety and performance. The careful analysis and validation of results ensure that the computational models developed using Rust are both robust and trustworthy, making Rust a compelling choice for modern computational physics.

1.5. Future Trends and Applications

The landscape of computational physics is continuously evolving, driven by advancements in computational power, new algorithms, and the increasing complexity of physical problems being tackled. In this context, Rust is emerging as a key player, poised to contribute significantly to the future of computational physics. As we explore the future trends and applications in this field, it is crucial to consider both the technological advancements and the challenges that lie ahead, along with the unique role that Rust can play in shaping these developments.

One of the most prominent emerging trends in computational physics is the growing importance of parallel and distributed computing. As physical simulations become more complex, involving billions of particles or intricate quantum systems, the need for scalable computing solutions becomes paramount. Rust's ownership model and concurrency features make it particularly well-suited for these tasks. Its ability to handle parallelism safely and efficiently allows researchers to develop simulations that can scale across multiple cores or even distributed computing environments without the common pitfalls associated with race conditions or deadlocks. As computational physics moves towards more ambitious simulations, Rust's role in enabling safe and efficient parallel computing is likely to expand, potentially making it a preferred language for high-performance computing (HPC) in this domain.

Another significant trend is the integration of machine learning and artificial intelligence with computational physics. Machine learning models are increasingly being used to accelerate simulations, optimize algorithms, and even discover new physical laws by analyzing vast datasets. Rust's growing ecosystem, including crates like tch-rs for PyTorch bindings and linfa for classical machine learning algorithms, positions it well for these interdisciplinary applications. The combination of Rust’s performance with its growing capabilities in machine learning suggests that it could play a pivotal role in the next generation of computational physics research, where AI-driven simulations become commonplace.

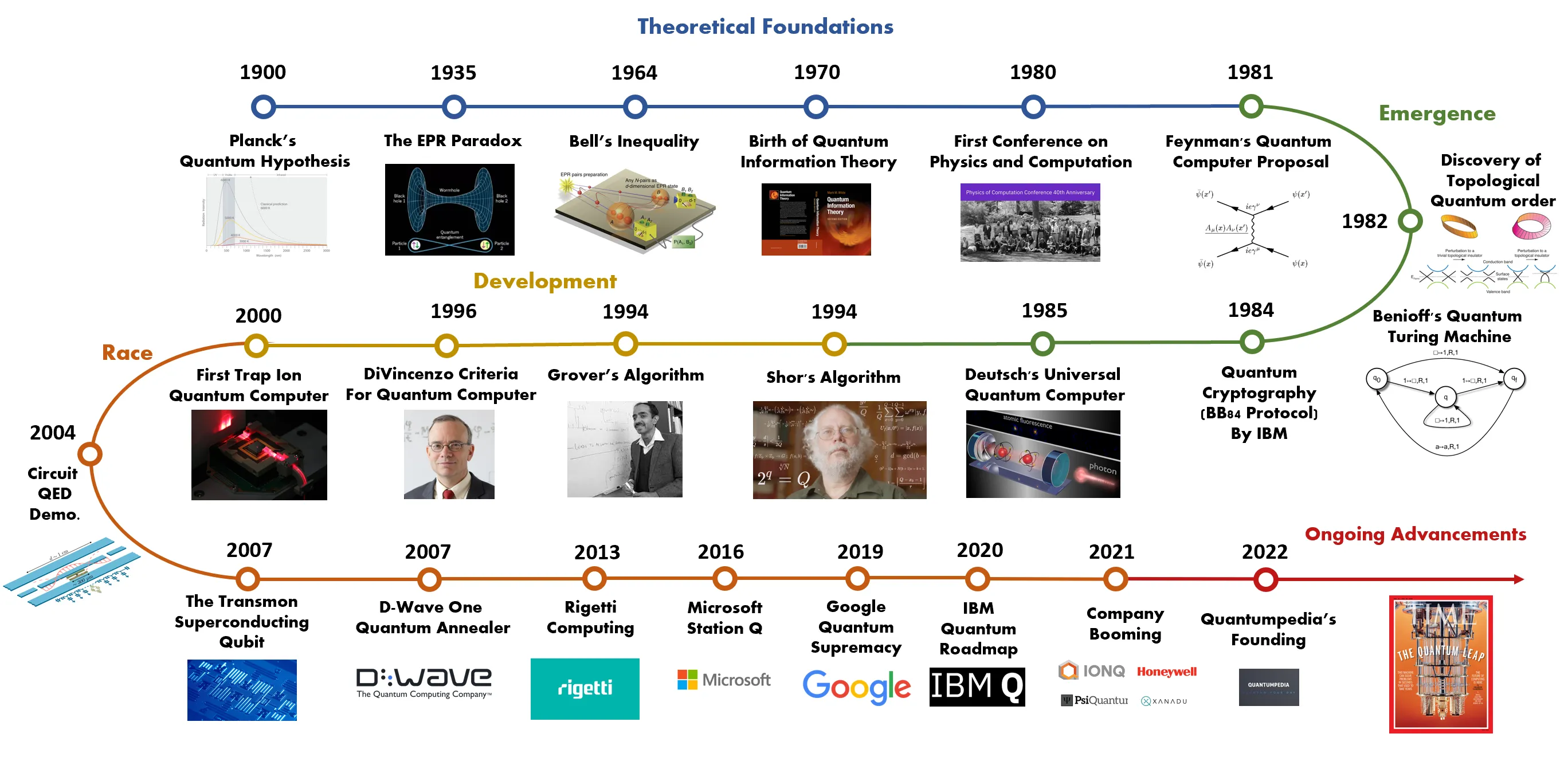

The historical journey of quantum computing.

Quantum computing is another frontier where Rust’s strengths are becoming increasingly relevant. As quantum computing transitions from theoretical foundational research to practical implementation, the demand for reliable, high-performance software tools is growing. Rust’s safety guarantees, particularly its memory safety and concurrency features, make it an excellent choice for developing quantum algorithms and simulators. Tools like Qiskit, which is traditionally associated with Python, are beginning to explore Rust bindings and integrations, enabling Rust to contribute to the quantum computing ecosystem. By leveraging Rust in quantum computing, researchers can ensure that their quantum algorithms are not only performant but also free from the common pitfalls of traditional programming languages, such as memory leaks and race conditions. This alignment with the needs of quantum computing positions Rust as a potential cornerstone in the development of quantum software infrastructure.

In the realm of life sciences, the concept of the Human Digital Twin is gaining traction, where detailed computational models of human biology are used to simulate and predict health outcomes. Rust’s precision and safety features are particularly valuable in this context, where the accuracy and reliability of simulations can directly impact human health. By utilizing Rust to develop these digital twins, researchers can create models that are both highly efficient and robust, capable of handling the vast amounts of data involved in simulating human biological systems. This approach could revolutionize personalized medicine, where treatments are tailored to the unique biological characteristics of an individual, and Rust could play a key role in making these simulations both scalable and trustworthy.

Additionally, Rust could see increased adoption in the development of real-time physics engines, which are essential for applications such as virtual reality, video games, and simulations in engineering and robotics. These engines require a delicate balance between performance and safety, particularly in environments where real-time processing is crucial. Rust’s ability to deliver high performance while ensuring memory safety and preventing crashes makes it an ideal language for these applications, potentially leading to more robust and reliable real-time physics engines.

However, the integration of Rust with modern computational tools and frameworks also presents challenges. Many existing scientific computing ecosystems are built around languages like Python, C++, and Fortran, which have a rich history and extensive libraries tailored for specific tasks. While Rust’s ecosystem is growing, it is still relatively young compared to these established languages. Integrating Rust into existing workflows often requires bridging the gap between Rust and these languages, whether through foreign function interfaces (FFIs), bindings, or embedding Rust code within other environments. This integration process, while challenging, also presents opportunities for Rust to establish itself as a complementary tool, bringing its safety and performance benefits to existing ecosystems.

Furthermore, the evolution of computational methods, particularly as they become more complex and data-intensive, will require languages that can handle both the computational demands and the reliability concerns associated with these methods. Rust’s continued development, particularly in areas like async programming, WebAssembly, and low-level hardware interaction, suggests that it will be increasingly capable of meeting these demands. As computational physics evolves, Rust’s adaptability and forward-thinking design may position it as a key language in driving the next wave of innovations.

In conclusion, the future of computational physics is set to be shaped by trends in parallel computing, machine learning, quantum computing, real-time applications, and life sciences, all areas where Rust has the potential to make significant contributions. While there are challenges in integrating Rust with established computational tools, the opportunities for Rust to advance the field are substantial. As computational methods continue to evolve, Rust’s role in this progress is likely to grow, offering a powerful combination of safety, performance, and modern programming features that will be crucial in tackling the complex challenges of tomorrow’s computational physics.

1.6. Conclusion

This chapter lays a solid foundation by exploring the core principles and applications of computational physics through the lens of Rust programming. It introduces the historical evolution of computational methods, highlights Rust's unique features such as its ownership model and memory safety, and demonstrates how these aspects contribute to solving complex physical simulations efficiently. By examining the setup of Rust for scientific computing and comparing its performance with traditional languages, this chapter provides a comprehensive overview of how Rust's advanced capabilities can enhance precision and reliability in computational physics. This foundational knowledge sets the stage for deeper exploration and practical application of computational techniques throughout the book.

1.6.1. Further Learning with GenAI

These prompts cover fundamental concepts, practical implementations, and advanced applications, focusing on both theoretical and hands-on aspects of the subject. By engaging with these prompts, you'll gain a thorough understanding of computational methods, Rust's role in scientific computing, and the nuances of implementing algorithms and models efficiently.

How have the foundational principles and evolving applications of computational physics shaped modern physical simulations, and in what ways do advancements in computational techniques influence the implementation of these simulations within contemporary computational tools and frameworks across different scientific domains?

What were the critical historical milestones and breakthroughs in the evolution of computational physics, and how did early computational methods, hardware advancements, and algorithmic developments pave the way for the sophisticated simulations and modeling techniques used today?

In addressing complex and high-dimensional physical problems, what specific computational methods have proven most effective, and can you provide detailed examples where computational physics has had a transformative impact on scientific research, technological innovation, or industry applications such as climate modeling or quantum mechanics?

What are the defining characteristics of the Rust programming language that make it particularly well-suited for high-performance scientific computing, particularly in comparison to established languages like Fortran, C++, or Python traditionally used in computational physics, and how do Rust's unique features contribute to both efficiency and safety in large-scale simulations?

How does Rust’s ownership model, alongside its novel approach to memory management and thread safety, enhance both the performance and reliability of scientific computing tasks when compared to other languages like C++ and Python, especially in scenarios involving parallel computing or resource-constrained environments?

In what specific ways do Rust’s compile-time checks, borrow checker, and memory safety guarantees contribute to reducing runtime errors and optimizing performance in computational physics applications, and how do these features address typical challenges encountered in scientific software development?

What are the step-by-step instructions for setting up a Rust development environment tailored for scientific computing, including best practices for configuring compilers, dependencies, and tools, and how can Rust be integrated seamlessly with existing scientific libraries (e.g., BLAS, LAPACK) and tools (e.g., Python, MATLAB) for comprehensive research workflows?

How do Rust’s core programming paradigms and syntax—such as ownership, traits, and functional programming constructs—facilitate the efficient implementation of complex computational algorithms in physical simulations, and how do these paradigms compare with other languages when solving advanced numerical problems in physics and engineering?

Which Rust libraries, crates, and frameworks are indispensable for numerical computing, linear algebra, and scientific simulations, and how can they be effectively applied to solve specific physical problems, such as solving differential equations, performing Monte Carlo simulations, or simulating quantum systems?

How can fundamental numerical algorithms, such as matrix decompositions, finite element methods, or fast Fourier transforms, be efficiently implemented and optimized in Rust for solving physical problems, and what are some concrete examples that demonstrate the performance and accuracy of these algorithms in real-world scientific applications?

What best practices and optimization techniques should be followed when developing Rust code for high-performance scientific computing tasks, and how does Rust's concurrency model, particularly through features like async/await and parallelism, contribute to achieving these optimizations in large-scale physics simulations?

How can Rust be effectively integrated with other programming languages and tools commonly used in scientific computing, such as Python (via FFI), C/C++ (through

bindgen), or even high-level tools like MATLAB, and what successful examples of cross-language integration demonstrate enhanced computational capabilities and performance?Can you provide detailed case studies or examples where Rust has been successfully employed to address computational physics challenges, such as complex simulations or large-scale data processing, and how do these implementations compare in terms of efficiency, performance, and maintainability with those developed in more traditional languages like C++ or Fortran?

How does the performance and accuracy of Rust implementations of specific computational algorithms, such as solving partial differential equations or performing molecular dynamics simulations, compare to similar implementations in languages like C++, Python, or Julia, and what factors—such as memory management, parallelism, or hardware utilization—contribute to these differences?

What methods, validation techniques, and testing frameworks can be employed to ensure the accuracy and reliability of computational models written in Rust, and how do these approaches compare to traditional validation techniques used in other scientific computing languages, such as unit testing, property-based testing, or formal verification?

What are the current and emerging trends in computational physics, such as quantum simulations, high-dimensional data analysis, or multiscale modeling, that could benefit most from Rust's features, and how might Rust’s safety, concurrency, and performance capabilities address the specific challenges these fields face?

How can Rust be applied to address large-scale and complex problems in computational physics, such as multi-scale simulations, real-time data analysis, or high-performance computing (HPC) workflows, and what real-world examples or projects illustrate its effectiveness in these challenging contexts?

What are the best practices for debugging, testing, and profiling Rust code within the context of computational physics, particularly in ensuring the accuracy and reliability of simulations, and what tools or methodologies (e.g.,

cargo test,gdb,valgrind) can help developers identify performance bottlenecks or logical errors in Rust-based physics models?How should documentation, version control, and long-term maintenance of Rust code in computational physics projects be approached to support usability, scalability, and collaboration within teams, and what strategies (such as writing doc tests or adhering to best practices in code commenting) are critical for ensuring effective and sustainable development practices?

What educational resources, online platforms, and community support are available for learning Rust specifically in the context of scientific computing and computational physics, and how can these resources—such as online tutorials, MOOCs, and the Rust community—be leveraged to enhance both beginner and advanced developers' understanding of Rust in these fields?

How does the growing Rust ecosystem and its active community contribute to the advancement of scientific computing, and what are some notable open-source projects, contributions, or collaborations within the Rust community that have significantly impacted the field of computational physics or scientific research in general?

Your commitment to understanding and applying these concepts will enable you to transform theoretical knowledge into practical, groundbreaking results, driving progress and discovery in computational science. Let each exploration fuel your passion for excellence and contribute to pushing the boundaries of what’s possible in scientific research and technology.

1.6.2. Assignments for Practice

These advanced exercises are designed to push the boundaries of your technical expertise and problem-solving skills. As you delve into these complex tasks, you will not only refine your understanding of computational physics and Rust but also develop a robust toolkit for tackling sophisticated scientific challenges.

Exercise 1.1: Comprehensive Historical and Technical Analysis

Objective: Conduct an in-depth historical and technical analysis of computational physics advancements.

Task: Use GenAI to compile a detailed timeline of significant milestones in computational physics, focusing on key innovations in numerical methods, algorithms, and computational tools. For each milestone, request a detailed explanation of the underlying technical principles and how they advanced computational capabilities. Include the impact of these advancements on specific physical simulations or scientific research, and provide a critical analysis of how these innovations have influenced current computational practices.

Exercise 1.2: Advanced Rust vs. Traditional Languages Comparison

Objective: Perform a thorough comparative analysis of Rust and traditional scientific computing languages.

Task: Request GenAI to provide a deep-dive comparison of Rust and C++ (or another language like Python) specifically for implementing high-performance computational algorithms. Focus on aspects such as Rust's ownership model, borrowing, and lifetimes, and how these features compare to C++'s manual memory management and Python’s dynamic typing. Ask for a detailed performance analysis, including benchmarks for specific computational tasks such as large-scale simulations, and discuss how Rust’s features contribute to or hinder performance in these contexts.

Exercise 1.3: Advanced Setup and Integration for High-Performance Computing

Objective: Master advanced setup and integration techniques for Rust in scientific computing.

Task: Engage GenAI in creating a comprehensive guide for setting up a high-performance Rust development environment for scientific computing. Include detailed steps for configuring Rust with advanced numerical libraries and integration with external tools such as GPU acceleration libraries (e.g., CUDA). Request specific examples of using Rust with popular scientific crates like

nalgebraorndarray, and provide code snippets and explanations for complex use cases such as multi-threaded numerical simulations or large-scale data processing.

Exercise 1.4: Implementing and Optimizing Complex Numerical Algorithms

Objective: Implement and optimize complex numerical algorithms in Rust.

Task: Use GenAI to walk through the implementation of a complex numerical algorithm in Rust, such as a high-order finite element method for solving partial differential equations. Request detailed explanations for the algorithm’s implementation, including code for handling boundary conditions and optimization strategies. Include performance profiling and optimization techniques specific to Rust, such as efficient memory usage and parallel computation. Compare the Rust implementation with those in C++ or Python, discussing the trade-offs and performance gains achieved.

Exercise 1.5: Rigorous Validation and Accuracy Assurance Techniques

Objective: Implement rigorous validation and accuracy assurance methods for Rust-based computational models.

Task: Engage GenAI to discuss and apply advanced validation techniques for computational models written in Rust. Request a detailed plan for implementing unit tests, integration tests, and regression tests for complex simulations. Include methods for cross-validating results with benchmarks from other programming languages and using analytical solutions where possible. Discuss strategies for ensuring numerical stability and accuracy, such as adaptive mesh refinement or error estimation techniques, and provide code examples demonstrating these practices.

Embrace the rigor of these exercises with determination and curiosity, knowing that mastering these skills will place you at the forefront of computational innovation. Your dedication to exploring and overcoming these technical challenges will pave the way for groundbreaking advancements in both theoretical and applied sciences.

Comments